Beth Lester

Helping Commissioners Serve Their Constituents

Fellowship at the US Department of Health and Human Services

Project Brief

The US Department of Health and Human Service's (HHS) Office of Business Management and Transformation (OBMT) was asked by one of the HHS's strategic committees to assist in the development of a new office within the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) as part of the Aim For Independence initiative. Aim for Independence proposed developing a center of excellence (CoE) focused breaking the cycle of poverty within families. As a national office, the CoE would interact directly with commissioners, helping commissioners serve their constituents achieve long term independence from government assistance. Our project team, consisting of myself, a member of OBMT with a concentration on design, and an undergraduate business student, was brought on to lead a human-centered design approach to the project in collaboration with a major consulting agency, and to then provide the committee with a "blueprint" for the proposed office.

Overview

Our team delivered a strategic plan to the committee detailing key activities for the office to execute, specific activities and messaging to avoid in the interest of maintaining users' trust and participation, and personnel qualifications and character recommendations. The office would focus heavily on integrating programs, measuring outcomes, promoting collaboration, and providing commissioners with tools to innovate within their state.

Using human-centered design methodology was an uncommon practice for the stakeholders in this project, and accordingly our team worked to overcome systemic wariness towards the human-centered mindset. As a result of co-creation sessions and compelling storytelling, we were able to establish rapport with committee members and effectively overcome these potential obstacles.

Roles I Played

-

Developed discussion guides

-

Conducted user interviews

-

Created and tested prototypes

-

Generated actionable insights

-

Outlined strategic plan

-

Presented insights and research to client via "paperpoint" prior to the strategic blueprint's development

Research

Design research tasks were split between out team at OBMT and the consulting agency's project team. Our team focused on the direct users of the office - the state commissioners, directors, and other individuals working with beneficiaries within the health/human services sector - and the consulting agency focusing on understanding experiences of beneficiaries of government assistance programs. The proposed CoE would serve all fifty states, and because each state has unique and varied needs it was important to ensure our users experienced a wide range of challenges and needs. To do so, our team prioritized having conversations with employees from states that fell at the extreme ends of the spectra we had identified as key to success in the health and human services sectors: the state's access to health and human service funding, the state's level of integration between health services and human services, and the state commissioner's level of internal support from the state's legislature.

Building rapport with users was vital to our research, but we faced pervasive skepticism as to both the sincerity and confidentiality of our efforts. Past experiences led many potential users to doubt that we had a genuine interest in hearing what they had to say and that their comments would not be used against them down the line. As a result, many declined participation or entered conversations with their guard up. Once rapport had been established, most conversations had to be conducted over the phone because of budgetary constraints. To ensure anonymity and to build trust, no photos or visual recordings were made during research. To begin all of our conversations, we explained who was on our team (many had never interacted with OBMT directly), what human-centered design is, and why they were so valuable to this process. From the start, we made it clear that they were the experts in the conversation, and that we were there to learn. Without understanding their experiences, we would not be able to recommend strategies for the office that would truly benefit them. As an intern, I was clearly a novice in the government, allowing me to ask questions that might have come off as silly or intrusive had my boss been the one asking.

The majority of our user research centered around learning about the experience of being an employee within the health and human services system at a local level. What is the most frustrating part of the job? The most rewarding? I've heard about other people experiencing this, what has your experience been with that? Once they were confident in our sincerity and the confidentiality of our conversations, users from commissioners to social workers shared detailed stories and offered more information than we had anticipated getting.

Understanding

Learnings, observations, and quotations from our conversations with users were synthesized using a say/do/think/feel framework. Information from the four categories were then re-organized into thematic groupings that were developed into actionable, impactful insights.

Our groupings and insights centered almost exclusively around systemic barriers to innovation:

-

Fears of failure, because the failure of an experimental program could cost the state funding in the future

-

Frustrations over the power dynamics between state governments and the federal government

-

Concerns as to how the proposed center of excellence might encroach on a state's autonomy

-

Lack of understanding at a state level of rules and regulations regarding funding provided by the federal government

-

Timidness of a commissioner hindered the whole state system's ability to innovate

|  |

|---|---|

|  |

|  |

|  |

|---|---|

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

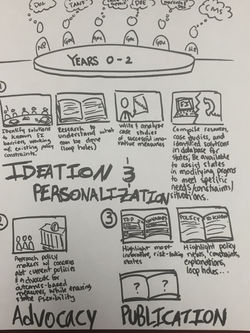

Iterations

Key activities that the office could potentially execute were prototyped as storyboards and diagrams and were tested with users over video-conferences when in-person conversations were not possible. Activities and questions such as, "What happens next?" and "Where are you in this story?" helped us understand what users' expectations were of the office.

As concepts were refined and added, storyboards became more detailed, and we were able to learn what were considered the scariest, most exciting, least welcome, and most aspirational aspects of the ideas we prototyped. Although we were unable to assess buy-in by sending mock emails, fliers, etc., we presented them to users during conversations and discussed them based on questions such as "What is your knee-jerk reaction to this?" and "What would have to be true about this event/service for you to sign up/use it?"

The concepts that generated the most excitement and conversation were those that:

-

Ensured the federal government would provide assistance when needed but...

-

...Recognized that the state leaders knew what was best for their constituents and included constraints on the CoE to maintain commissioners' and control over innovation in their state

-

Encouraged risk-taking by eliminating the fear of repercussions

-

Provided guidance navigating funding rules and regulations, especially with a focus on understanding how to innovate within these constraints

-

Promoted the break-down of funding silos

-

Created avenues for collaborating with other states, implementing successful programs across state lines, and establishing standards of excellence

Solution

The "blueprint" our team provided to the strategic committee and ACF detailed key activities for the proposed office, specific activities to avoid, and important qualities of prospective leadership. We recommended that the office, first and foremost, encourage healthy risk-taking by commissioners and directors. Strategies for doing this included:

-

Providing no-risk, short-term grant funding for trying new programming without fear of repercussions. Our strategy included an annual or semi-annual call for grant applications, with a few states being given funding for new programming each year. Applications would include rationale for the new programming, background supporting the proposal's strategy, and proposed methods for measuring outcomes. Most importantly, grantees whose plans did not lead to the outcomes they had expected would not be penalized and would be able to apply for new funding at the next call.

-

Giving commissioners and directors autonomy to ask for help as they saw fit, rather than having someone from Washington, D.C., come in to problem-solve on their behalf. Though ACF and the committee had originally come to us with the belief that a "SWAT team" approach - sending federal employees from the CoE in to states to provide assistance - would work well, our findings indicated the opposite and we noted this in our strategy. Instead, we designed a system of "federal navigators" to whom state leaders could turn for assistance when they wanted help. These navigators would be able to provide a broad range of consulting services, from problem identification, to program design, to guidance regarding innovation within the constraints of federal rules and regulations

The blueprint further discussed strategies that could be used to build rapport with users and alleviate fears of insincerity, as discussed above. Phrases such as "SWAT Team" instilled fear of an overbearing CoE and discouraged state leaders from wanting to engage with the office. Messaging about the CoE needed to reflect a culture of support, trust, and encouragement. Along with this messaging, we gave recommendations regarding important qualities of a leadership team for the office. Our strategic blueprint emphasized the importance of the CoE's leadership being neutral parties, above reproach. Leaders needed to be able to take pushback from the federal government for any "failures" at a state level that came as the result of trying new programming, providing a physical and emotional buffer for states. Furthermore, CoE leadership needed to be willing and able to defend risk taking, understanding and advocating for small failures as learning experiences, then helping states grow from these learning experiences to ultimately improve programming .

Additionally, we detailed core values of human-centered design methodology, such as iterative testing of concepts on a small scale, taking "failures" as opportunities for continued learning, and strategies to ensure a continuous feedback loop with users. We viewed general lack of familiarity with design thinking as a potential barrier to the CoE's success and wanted to provide as much opportunity for growth as possible. Our team recognized how radical many of our proposals would be daunting to a risk-averse budgetary committee, so we emphasized framing small-scale prototype testing as a risk-management solution and included strategies for minimizing financial impact of prototypes. The blueprint further encouraged the CoE itself to be run as a prototype at first, starting with a few states, then tweaking and expanding as kinks were worked out and the office gained credibility and support.